I was at the library checking out a book on sling and slingstone archeology, and next to it was a book on boomerangs! So of course I got it. My dad had a nice wood boomerang when I was a kid, and I played with that and some plastic ones at one point too. They are much harder to get to return than you might think. I never got the wood one to work, and I was always scared it would hit me on returning.

We tend to think of the boomerang as a toy, or novelty, but it was a nearly-ubiquitous and very important weapon, tool, and religious object for aboriginal Australians (Jones 1996). Every hunter had at least a few, often many of various designs for many functions (Jones 1996). They called them “karli,” “belo,” “iringili,” munartajartu,” “pirrkala,” “wallanu,” “warlanu,” “warraka,” “wana,” “murrawirrie,” “ngamiringa,” “yarrakoodakoodari,” “karra,” and many more names, but most commonly, “kiley,” with different types having different names, and for different language groups (Jones 1996). Aborigines in Tasmania did not have boomerangs, nor did most in the tropical north or those in the western central desert regions (Jones 1996).

There are two main categories of boomerangs: returning and non-returning (Jones 1996). The latter are kind of like the rabbitstick that was a common weapon of American Indians to throw at rabbits and small game. This type of weapon is a major improvement over just a plain stick since they are carved thin and have a bend in one end or near the middle. This shape makes them go much further, straighter, and have more force upon impact. These sticks were found in many aboriginal societies, as well as ancient Egypt (Jones 1996).

rabbitsticks or throwing sticks, including some returning boomerangs, from Tutankhamen’s tomb (Jones 1996)

The non-returning boomerang was perhaps more common than the returning form, the latter which may have been mainly used for small game hunting, hitting flocks of birds or to mimic a hawk in order to make waterfowl fly low into a net (Jones 1996, see more on this down below).

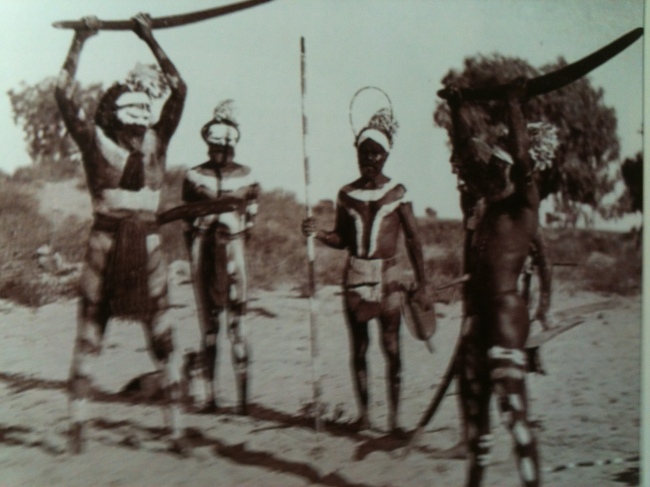

The non-returning and returning boomerangs were used for many purposes other than throwing for hunting: they were used for hand to hand combat (esp. the longer, straighter ones), a knife, a hammer or club, a digging tool, making fire by friction (fire plow technique), for clapping together as a percussion instrument, and for many ceremonial or religious purposes (Jones 1996). The diversity of shapes reflects their diversity of uses, and for hunting, there was many different shapes depending upon the prey and the desired flight path.

The returning boomerang was sometimes thrown over a flock of waterfowl, the boomerang having a hole drilled in one end to make a whistling sound like a hawk, while hunters also made a hawk cry, in order to flush the birds towards a low net that had been previously strung across the body of water, since the boomerang-hawk made them fly low, and rapidly in fright. Upon hitting the net, hunters at each end would let it drop, trapping the birds.

The returning boomerang was also thrown into flocks of birds, being superbly effective with its high velocity and eccentric flight path making it very difficult to dodge by the birds, though the boomerangs flight path would be well-known to the hunter (Jones 1996). Of course, whenever the returning boomerang hit its mark, it fell and did not return.

The returning boomerang was used also for games and sport by the Australian aborigines, some similar to today’s contests with boomerangs, where one person throws and tries to get it to perform particular flight patterns like figure eights, or return accurately to a circle drawn around the thrower, or hit a peg (Jones 1996). A game was played mimicking war, where a line of warriors threw one by one at eachother, holding shields, and trying to dodge or block incoming boomerangs, which was difficult given their erratic flight path (Jones 1996).

Depending upon how it was thrown, a boomerang can have drastically different flight paths:

One special type of (non-returning) boomerang was biconvex, short, and wide, with a pointed handle and sharp edges (Jones 1996). This type was thrown into water to kill fish near the surface. This type was also made with metal when it became available (Jones 1996).

Some boomerangs were cross-shaped, others had hooks on one end, but mainly they varied by length, angle, sharpness of ends, and thickness, wood, and weight.

Often boomerangs were incised and / or painted with maker’s marks or ancestral designs. One common incising was fine flutings down the length of boomerangs (Jones 1996). I suspect this may have had an affect on performance, since overly-smooth boomerangs don’t fly as well. The dimples on golf balls really enhance their flight, and this may be analogous with these flutings (Jones 1996).

Once boomerangs became a popular tourist item, aboriginal manufacturers starting focusing more on carving and painting designs than quality of functional design (Jones 1996).

Modern boomerangs are often manufactured, and are made of plywood, plastic, or cardboard to be a safe toy (Jones 1996). Some are in made in novelty shapes (Jones 1996). Competition boomerangs include tri-bladed designs for “fast catch” events, while unequal-limbed designs (also often found in aboriginal boomerangs) are used for “maximum time aloft” competitions (Jones 1996).

The returning boomerang uses two opposite-facing airfoils blended at the center, a slight positive dihedral, and a bend in the middle around 107 degrees (lefties need to reverse the side of the airfoils). The fly using the principles of gyroscopic stability, gyroscopic precession, Bernoulli’s principle of differential air pressure and the Coanda effect along with Newton’s laws of motion.

http://www.researchsupporttechnologies.com/boomerang_site/boomerang6.htm

Normally, a boomerang is thrown overhead, “V” pointing forward, held nearly vertically, gripped in the hand or between the thumb and forefinger. The flat side faces away. Throw at about a 45 degree angle from the incoming wind. A boomerang can be tuned by test flights, then altering the wing shapes to correct the flight errors. See the link below for more info on tuning.

http://www.angelfire.com/nc/conally/manual.html

I collected some nice bent branches of madrone the other day, and I’m going to carve some traditional returning boomerangs! I’ll post a photo-methods record when I do.

Here is a great photo documentation blog post about making a non-returning boomerang (it’s an awesome blog in general too): http://naturalskills.wordpress.com/2011/06/17/boomerang-build-a-long/

REFERENCE:

Jones, Philip. 1996. Boomerang: behind an Australian icon. Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, CA.