Belgian Shepherd looking glorious climbing a California bay laurel tree in Wildcat Canyon of the East Bay Hills.

Dog – Canis lupus familiaris

The oldest known records of dogs in the Americas are from over 13,000 years ago in Hell Gap, Colorado, and Agate Basin, Wyoming (Snyder and Leonard 2011). Dogs were used by American Indians for pulling sleds, pulling travois, carrying packs, assisting in hunting, for eating, ritual sacrifice, and for weaving their fur into high-quality blankets (Snyder and Leonard 2011). Dogs were also appreciated by the Indians as companions and sentries. Many dogs have been found buried at archeological sites just as dead humans were buried, sometimes even with offerings (Snyder and Leonard 2011).

American Indians had large, strong, wolf-like dogs, who howled rather than barked (Snyder and Leonard 2011). Genetic analyses suggest there were multiple independent origins of dogs from wolves, and it is likely that back-crossing with wolves, coyotes, and even foxes occurred (Snyder and Leonard 2011). Whether this genetic introgression occurred via intentional breeding, by “accident,” or feralization is unknown (Snyder and Leonard 2011).

Some of the earliest archeological evidence of domesticated dogs being used for a particular purpose is pulling sleds over ice and snow in Siberia and Alaska (Snyder and Leonard 2011). In, fact, dogs probably pulled the sleds that carried the very first humans to populate the Americas! Good doggies! Ten to twenty thousand of their descendents were mercilessly slaughtered as policy by the Canadian police in the mid-1900’s (http://fortheloveofthedogblog.com/news-updates/the-inuit-sled-dog-killings).

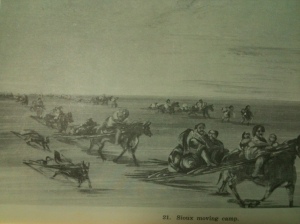

Dogs were used to carry packs extensively in the Western Arctic, and were a important fixture of the bison hunting Plains Indians societies, where they pulled travois, especially when moving camps (Snyder and Leonard 2011). Such dogs could pack loads of 40 to 45 pounds and pull loads up to 75 to 100 pounds (Snyder and Leonard 2011). They often carried firewood, meat, tents, and other supplies (Snyder and Leonard 2011).

Belgian Malinois magnanimously carrying backpack full of quartz crystals near Inyo National Forest, CA.

Not all dogs would suffer a load, being too defiant, young, or small, and these “freeloaders” would often gleefully harass the burdened dogs en route (Catlin 1973:43-44). A village of 500 teepees might have several thousand dogs carrying loads, in addition to over a thousand horses (Catlin 1973:43-44). Their travois (simple drag-sleds) were made from two poles about 15 feet long with the thinner ends secured to the dogs’ shoulders and the butts of the poles dragging on the ground (Catlin 1973:43-44). A short bracing pole was tied to both long poles just behind the dog, and a bundle or wallet was secured to these poles behind the dog (Catlin 1973:43-44).

These poles were almost certainly from the lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta var. latifolia) that grew in the nearby Rocky Mountains. Such pines supplied the poles for the lodges and teepees of many Plains and Rocky Mountain Indians. Poles were cut from trunks in the winter or early spring while the sap was down, their bark removed, and left to weather until fall, when they were collected for use (Peattie 1950). Such poles were preferred since they were very light, of nearly uniform diameter throughout their length, and extremely hard, stiff, and nearly impossible to split (Peattie 1950). Plains Indians would not use cottonwood or willow, instead they traveled all the way to the Rockies or bartered with Rockies tribes for these poles (Peattie 1950).

Painting of Sioux Indians moving camp, drawn first-hand by George Catlin in the 1830’s (Catlin 1973:Plate 21).

The accounts of Plains Indians’ relationships with dogs came after the introduction of the horse plus the fur and hide trade. Dogs may have been much more important before horses were available. In the later years of the Plains Indians, dogs were reduced to being an emergency food source, no longer being esteemed highly enough to feed and maintain (Snyder and Leonard 2011). Among the Plains indians, women were the chief companions of dogs, using them to gather firewood and other materials, and leading the burdened dogs when moving camp (Snyder and Leonard 2011).

On our recent backpacking adventure at Cache Creek BLM wilderness in CA, Emily’s dog Neptune cheerfully bore our heaviest load: water. That pack must’ve weighed over 40 lbs… what a hoss!

Dogs were used in hunting throughout the Americas, especially in forested areas (Snyder and Leonard 2011). They were not used much for hunting in the Plains (Snyder and Leonard 2011), but they may have been used more there before the introduction of the horse. Eskimos trained their dogs to find seal breathing holes (Snyder and Leonard 2011). Subarctic Indians had dogs assist in hunting bears, beavers, and even musk-ox and polar bears (Snyder and Leonard 2011). The latter two were highly dangerous, and dogs chased and brought them to bay for the Indians to kill (Snyder and Leonard 2011). In heavily wooded areas, dogs were used routinely to hunt turkey, deer, and squirrels (Snyder and Leonard 2011).

In some areas, dogs (such as the Mexican Hairless) were raised specifically for eating, while in other areas dogs were only eaten as part of certain ritual feasts (Snyder and Leonard 2011). In some areas of the American northwest, dogs were bred for long thick coats that Indians sheared, spun into yarn, and wove into blankets of high status and value (Snyder and Leonard 2011).

The fur of my dog Kitsune would make for a good blanket. But she’s a terrible pack dog now that she’s learned how to throw her backpack off by running, then suddenly stopping with her head ducked and front legs out front, like the “down dog” stretch pose… that cunning, load-shirking bitch.

No other species has lived alongside humans for as long as the dog, since cats were first domesticated (or more accurately, domesticated themselves) at most ten thousand years ago, when people began to store large amounts of grains that attracted abundant rodent prey of cats. It’s no wonder so many people instinctively feel a kinship and understanding of dogs. Their social structure and hunting methods are very close to humans, making them perfectly suited for companions and assistants. Dogs are the only other species (I know of) besides humans that exhibit cursorial hunting; running after prey for as long as it takes, and finally catching their exhausted quarry since we both have such incredible long distance endurance. The !Kung bushmen in Africa still run down gazelles in this manner that is also displayed in many nature documentaries showing wolves hunt.

So If you’ve got a dog, please use any knowledge I may have given here to reinvigorate the human-dog bond; go running for hours, get it a backpack and have it haul water. Try to understand what makes your dog happy, and it just might infect you!

References:

Catlin, G. 1973. Letters and notes on the manners, customs, and conditions of North American Indians. Dover Publications, Inc. New York, NY.

Peattie, D. C. 1950. A natural history of western trees. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston MA.

Snyder, L. M., and J. A. Leonard. The diversity and origin of American dogs. Ch. 21 In B. D. Smith (Ed.). 2011. The subsistence economies of indigenous North American societies: a handbook. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, Washington, D.C.